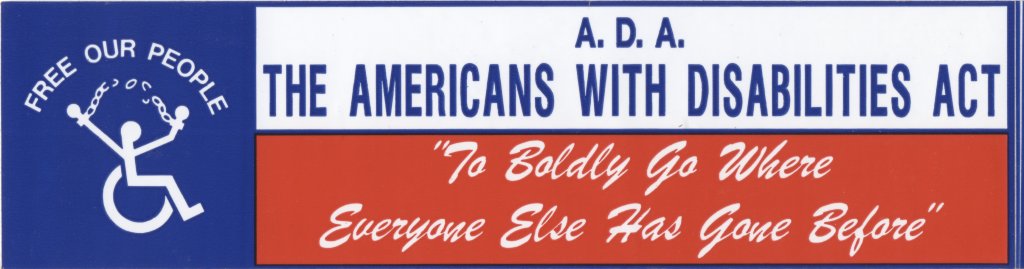

“Boldly going where everyone else already goes” is the slogan of the disability activist group ADAPT. They began their work in 1990 by working to make buses wheelchair compliant, and they continue their vital work of protecting those with disabilities to this day. Their seemingly outlandish motto illustrates what it means to provide access within the built environment in the United States. It reveals that because of a history of exclusionary design practices, a level of modification must happen for the public realm to become genuinely “public” for everyone.

1 in 4 adult Americans has a physical, mental, or sensory disability – a physical disability being the most common. A physical disability is defined as “hav[ing] difficulties getting around, walking or climbing stairs.” Yet, despite the number of people with disabilities, more than 50% of commercial buildings and 60% of homes were built before 1980; prior to the implementation of the Americans with Disabilities Act of 1990. These statistics imply that most buildings in the United States are not accessible via ramps, have wide doors, or even door knobs that can be easily grasped and opened. 65% of curb ramps and 48% of sidewalks are not ANSI compliant. This statistic is even more significant for neighborhoods that rely on bus stops, with 71% of the sidewalks lacking curb cuts and 76% of the bus stops lacking shelters.

Simply put, most of the existing built environment is not accessible to a significant number of Americans. Adding ramps, curb cuts, and brail signage are instrumental in making our built environment accessible. Still, they are merely the tip of the iceberg for providing equal experiences in public spaces/life. We must catch up on updating and retrofitting the existing public environment and propel new construction to be even more inclusive, implementing Universal Design.

There are many preconceived notions about modifying a historic structure. Many people think preserving a building means keeping it 100% exactly as it was, without altering the structure, even providing access via ramps, door widening, lighting, or audio aids. These assertions are entirely false. Revising building/environmental existing conditions can range from simply adding a ramp to the front of someone’s home to more complicated interventions, such as adding an elevator to a historic university library. They can all be achieved within the context of historic preservation.

The role of preservationists and designers is that of stewards of change. Change is inevitable, and we are responsible for directing that change on a path that provides the most significant push forward while respecting the past. The National Park Service has produced a series of briefs written as guides for the preservation process; Preservation Brief #32 outlines guidelines for providing access as renovations occur. The three-step approach requires that the implementation of access protects the integrity and historic character of the historic property by:

- Review the property’s historical significance by considering its importance and character while examining how ADA-compliant features can be implemented.

- Assess the property’s existing and required level of accessibility. For example, President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s home was modified for his wheelchair, which still allows wheelchair use today. While the modifications made in the 1940s might not meet today’s ANSI standards, they are a character-defining feature and still provide the necessary access for people to visit the FDR home and convey an essential aspect of FDR’s home life. Supplemental access can be provided to meet universal access needs (i.e., lighting, brail signage, grip strips on stairs, etc.) while maintaining the home’s primary character-defining features.

- Evaluate accessibility options within the preservation context. This means providing access to the main or prominent public entrances, access to goods, services, programs, restrooms, amenities, and secondary spaces. If the roof is not a programable space, then there is no need for the roof to be accessible other than for maintenance.

Each entry point is situational and requires careful analysis of how to provide access; managing alterations and equal access is a considerable part of a designer’s job in historic spaces.

An example of accessible design in a historic space is the Cellhouse Plaza on Alcatraz Island. The entrance was historically one step above the plaza to enter the building, a grade change of roughly 7 inches. To give building access to people in wheelchairs, with strollers, or with physical mobility issues, a solution was devised to create a non-conventional ramp that fit within the setting. A semi-circle was created, radiating from the entrance, with the entrance being a high point and the edge of the circle meeting the grade of the plaza. The newly added material was concrete, like the historic plaza material, but was colored differently, so it could not be mistaken as part of the original design. This creates a seamless, unobtrusive, universally accessed entrance to the building that respects the history of the building by preserving as much of the character and original fabric of the environment as possible. The slope was 1:23, which is very shallow, making the entrance effortlessly accessible.

Access to everyone should be a priority for anyone working within an existing building. Every modified building is one more place for inclusivity, allowing people to enjoy life without complications. Moreover, accessibility is the law; it is a civil right that people have fought for and is invariably a benefit to the inhabitants of a building. Everyone will benefit from accessible buildings as age, accidents, pregnancy, and other events shape our lives. Creating sustainable spaces prepared for the changing inhabitants will require fewer modifications and lower environmental impacts in the long run. Extending the life cycle of a building by adding an elevator will be less impactful than demolition and new construction, and it will keep the current inhabitants in place longer.

As preservationists and designers, we must consider a multitude of experiences when creating building designs. We have to ensure that all have the opportunity “to boldly go where everyone else goes.”